iOS Games

Lazy Nostalgia: How Mobile Gaming Could Be a Real Work of Art

The discussion of whether video games are art or not is one no longer worth having. Games are a form of creative expression and those of us who continue to play them must be getting worthwhile experiences – emotional, mental, or otherwise – out of doing so. The more valid question is whether games are good art or not because, well, not a lot of modern games particularly overextend themselves when it comes to trying to take the medium in unique directions and mostly we’ve got boring, samey games.

The discussion of whether video games are art or not is one no longer worth having. Games are a form of creative expression and those of us who continue to play them must be getting worthwhile experiences – emotional, mental, or otherwise – out of doing so. The more valid question is whether games are good art or not because, well, not a lot of modern games particularly overextend themselves when it comes to trying to take the medium in unique directions and mostly we’ve got boring, samey games.

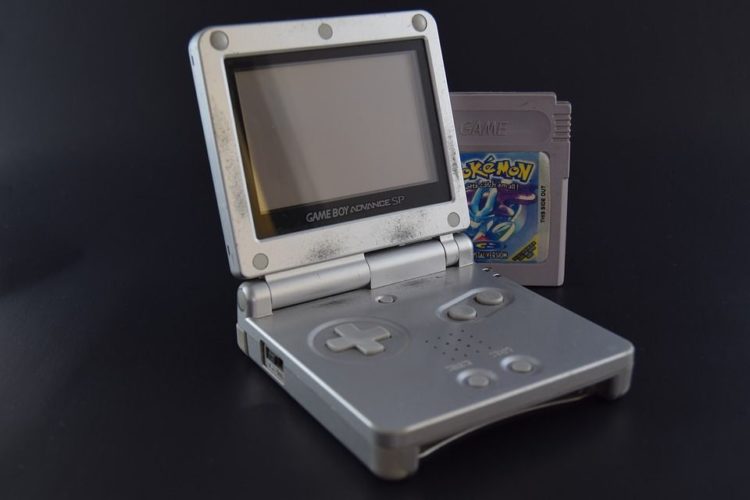

Much of gaming’s most bizarre, unique, creative, and artistic concepts came from the eighties and early nineties when a title didn’t need several bank accounts emptied into it for it to stand alongside other interactive works. It was more a question of whether one had the skill to work with this fledgling medium and whether they had any idea at all of what to do with it. As such, our gaming forefathers are a decidedly odd bunch, from Mario – a plumber eating mushrooms to grow bigger and jump on turtles – to Guybrush Threepwood, who is named Guybrush Threepwood.

Right now, there’s the potential for a second gaming renaissance. Big budget titles, the majority of which feature hulking manly-men hurting each other with various weaponry, may at present be the face of this medium, but, beyond those, a veritable maelstrom of indie developers have taken to fashioning more modest, yet no less worthwhile titles. This is a fantastic time to be involved in games as, in some respects, we’re back to where we once were. A game can once again be produced with only a few people, some big ideas, and a small budget. Even better, there are more platforms than ever before for these games and, with mobile gaming, the people who discover them can be gamers and non-gamers alike.

Android gaming provides an especially fertile platform due to its lack of a vetting process. Without moderators or the need to work with publishers, anybody can theoretically cobble together a game with the express notion of working toward a vision, rather than a specific demographic. Players are currently more than willing to try out titles knowing they may not be getting something visually or aurally comparable to an AAA console game. In fact, people often flock to these humbler titles specifically for this reason. We all want to see something different. And these indie games are different. Because they’ve adopted a different set of clichés.

It’s depressing enough to witness the state of much of modern mainstream gaming, which (though the roots obviously trace back further than this), can essentially be viewed as the direct product of Resident Evil 4, Uncharted 2, Grand Theft Auto III, and Half-Life. While these were all fantastic, game-changing games, they resulted, predictably, in numerous copycats. Some recent games have taken the formulas established by these titles and done impressive things with them (for example, Spec Ops: The Line seemed to be a criticism of the third-person cover-shooter and series like Infamous and Saints Row took the inherent insanity of sandbox games and indulged in it all the more), but more often we just get lazy attempts at cashing in on current, popular genres.

Since smaller games can’t ever hope to have the cinematic presentation expected from that of the mainstream, we instead end up with various games lazily inspired by the titles of yesteryear. For one, we get a lot of retro pixel art, which usually does nothing particularly new with the style, content to simply recall a bygone era. Games like Fez and Spelunky go for a blocky look that, at one time in gaming, was a necessity due to hardware limitations. Now, it simply looks lazy. You can almost see the ease with which environments were pieced together with a level editor.

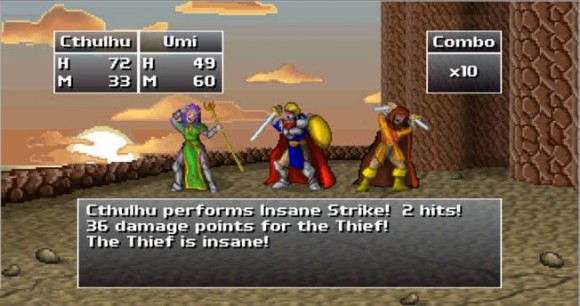

Obviously, this is the game these guys wanted to make and this would be fine if a game such as Cthulhu were satisfying a niche, but retro homages (if we choose to label them so kindly) are closer to the norm and titles branching out past this approach are the anomalies. Obviously there’s a benefit to small teams with small budgets using simplistic art, but this is really no excuse for doing a blasé copy job. The unfortunate thing is that the retreading of old concepts triggers nostalgia within us older gamers and that feeling probably suffices for many; simply making a gamer wistful may seem like an artistic feat in itself. However, the joy of the games these titles are ripping from came from the fact was that they were breaking new ground and trying out new ideas with almost every release. This new approach of reheating old game styles is a cheap and in no way novel method of getting inside our hearts.

It’s not as though the past should be completely ignored, but our games should be building upon history, not repeating it. A perfect example of a game doing this right is Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP. Visually, it’s influenced by the pixel art of games from the Commodore 64. However, Superbrothers takes this style and puts its own spin on it, resulting in instantly eye-catching visuals that recall past games while also creating something entirely new. The graphics look as though they took a lot of work with each screen in the game unique to the next, but then this shouldn’t be surprising. Making good art is hard work.

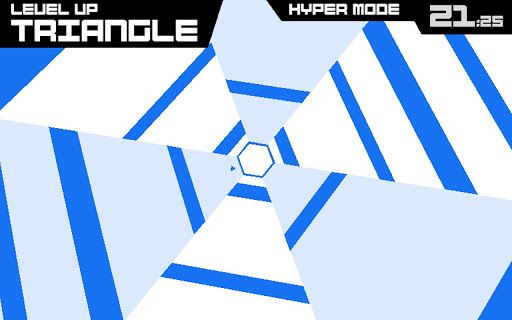

But that isn’t all there is to the game. Superbrothers recognizes that technology is changing and that our interactive media must follow suit. As such, the game actually takes into account the fact that it is being controlled through a mobile device with a touch screen, requiring you to solve puzzles with multiple fingers and including inventive little touches like having you turn your device vertically to unsheathe your sword. The beauty of Superbrothers is that its look and the way it’s played are so completely fresh that it brings new concepts to those who typically game as well as those who do not. There are so few games that I feel confident in being able to recommend to gamers and non-gamers alike, but this is one of them. Again, there are references in it that will make old-school gamers smile, but being a gamer is not a prerequisite to enjoyment. This is art more people can appreciate because there are various ways to appreciate it. This is good art.

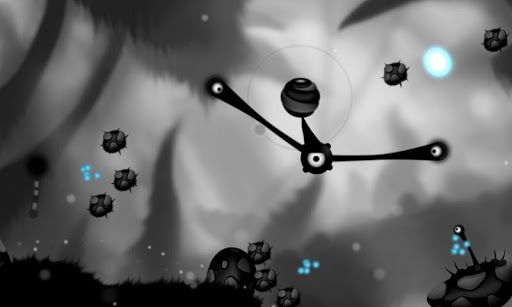

The problem of alienating non-gamers is something of an epidemic in this industry and is the result of a number of factors. A big part of it is that so much of gaming is just a boring copyfest. If this stuff hasn’t been intriguing to previously uninterested parties, why would revisiting it make them care now? Additionally, the indie scene has even managed to quickly create new clichés as there seems to be a new movement of developers functioning under the notion that black-and-white graphics coupled with a semi-morose, piano-centric soundtrack automatically equates to being artistic.

Contrastingly, Contre Jour feels like it chose two random elements and stuck them on top of uninventive game mechanics that are immediately reminiscent of another recent (and admittedly fun) game, Cut the Rope. But Cut the Rope just feels like a whimsical little puzzle game that wasn’t aspiring to be morose or moving whereas Contre Jour has the audacity to suggest you put your headphones on at the start for the most engrossing experience. Of these two, Cut the Rope is actually the better work of art. It’s basic, fun gameplay, so its visuals and music follow suit. Contre Jour’s presentation does not mesh with its gameplay. It just feels like the art, graphics, and gameplay happen to be in the same place at the same time by accident.

The problem here is that this sort of approach fools a lot of gamers because we’re so used to our art being subpar. Googling Contre Jour will reveal numerous pieces citing the game as an example of an artistic achievement in gaming when it’s actually just an average (though essentially solid) physics puzzle game that sounds and looks “sad.” Not that black-and-white graphics can’t be artistic. For example, the platformer, Limbo, used them effectively, but Limbo was centered on the depressing concept of a static existence beyond death and, again, this is working toward a singular vision. Minimalist, colorless environments seem appropriate in this case. Also worth mentioning is that Limbo opts for an ambient soundtrack consisting mostly of effects rather than music. It doesn’t try to force you to feel anything by cramming strings and pianos onto its soundtrack. Those might work in some media, but the developers of Limbo recognized their theme was minimalism and loneliness and created their soundscape in service of that.

When these things work together well, it’s something more of us, not just us gamers, are able to feel. Too many of us too deep into this medium to be objective are easily moved (or think we’re moved) by seeing nostalgic refurbishments of images and ideas from our past or by the removal of color from graphics or the addition of pianos to soundtracks. However, for people to whom video games do not yet seem a viable art form, this stuff is either completely foreign or just average. In the world of film, Kevin Smith pulled the black-and-white retro look way back with Clerks and sad scores show up in almost every dramatic picture out there. If we want to make something more worthwhile—both for those who typically game as well as those who do not—we need to put sincere effort into considering what specifically our medium can do that will be unique, novel, and beautiful.

Cherry-picking concepts and art from other works and dropping them into your own is a bad way to do art. As a developer, you should work toward a singular vision that would be fun and interesting for you as a gamer, sure, but even just as an individual. What fascinates you? What interests or troubles you? What are ways you can express or address these issues that you cannot in other media? And remember that, with mobile gaming, you’re working with a portable platform that allows for heretofore unexplored methods of interaction.

The tools to make something new and better are available, so stop trying to make art that just makes gamers remember older, better art. Make something actually interesting. Make something genuinely enjoyable. Make something beautiful. Make something fun. Make something great. Make good art.

Article by Joe Matar, lead contributor and reviews editor at Hardcore Droid (www.hardcoredroid.com). He hasn’t stopped gaming ever since he first played Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders for the Commodore 64. He is always on the lookout for solid game narratives and never gets tired of writing about the games that do it right. Or terribly wrong.

Featured

Horse Racing Games For iOS

Horse racing is a globally spread sport with billions of fans worldwide. The thrills of the races and the excitement of the betting make horse racing quite popular among adrenaline rush seekers.

However, unlike other sports like football or basketball that you can actually try in your backyard, becoming a racehorse rider is out of reach for most people. But all hope for our fellow race lovers is not lost and the gaming world comes to the rescue.

We are talking about horse racing simulation games where you can pick or breed your own horse, participate in online racing tournaments, earn prestige, take care of your horse, and much more.

Horse racing video games are perfect when it comes to getting the bigger picture of the sport and familiarizing yourself with other aspects apart from racing, like stable management, breeding, and finance management.

On top of that, horse racing video games can help you understand how the sport works, which may help you with the next bet you make on TwinSpires.

Fortunately, there are plenty of horse racing games for iOS, and in today’s article, we will highlight some of the best that you should try.

Rival Stars Horse Racing

This is a game made by a legendary horse race video game developer called PikPok and it is without a doubt one of the best horse racing games available for iOS right now.

The graphics look incredible for a mobile game. They are quite realistic, and the horse movement and the design of the tracks also give you the feel that you are participating in a real-world race.

Rival Stars Horse Racing has quite a fast pace, where you can complete some quests and upgrade your stable, but the focus is on the races, as it should be.

When we talk about the racing part of the game, every racetrack that you unlock offers something new. You get to race at different lengths and surfaces. But let’s focus on the important part, race mechanics.

You can steer the horse, brake, and activate their sprint ability. The horse’s performance is based on multiple factors such as ground consistency, position, race length, previous races, and much more.

Rival Stars Horse Racing also has a quite good breeding, training, and managing system. On top of that, there are many different horse coat colors and breeds. Unlike other games like Zelda where you can get a gold horse, Rival Stars Horse Racing focuses on realism. All of the horses have natural coat colors and traits.

You get to collect or breed horses, transform foals to feed, and upgrade facilities to unlock more options to progress.

The only thing that is missing from the game is the audience on the races since the race courses feel a bit empty with nobody around.

Horse Racing Manager 2024

This is a game that has a rather different approach than Rival Stars Horse Racing. It is focused more on the managing part of horse racing rather than on the actual gameplay and racing. You are in control of your business operation and your goal is to succeed in the world of horse racing and earn money.

You don’t have an impact on the races, and you cannot control your horse. The races are simulated, and the outcome depends on your horse’s stats and abilities.

That’s why horse training, and breeding a champion horse play a really important role in the game.

The best thing about Horse Racing Manager 2024 is the ability to race online. There are live PVP races that occur every 5 minutes and everyone can participate in them.

This is the perfect game if you want to learn what’s happening behind the curtains of horse racing as a sport. You are in control of your breeding rights that you can sell, as well as the age and career path of your horse.

It is an interesting game, especially for those who are not afraid of data and analysis.

iHorse Racing

This is a similar game to Rival Stars Horse Racing but with worse graphics, and fewer options. This game has multiple features like horse training, stable management, horse auction, race entries, CLU-jockey hiring system, and world jockey ranking, and you can connect your Facebook profile to invite friends.

To be honest, the graphics and gameplay of the game are fun and engaging, but I’d still go for Rival Stars Horse Racing, especially if you like a more realistic horse racing game.

Pocket Stables

Let’s drop down all the realism and focus on some retro 2D gameplay. For all retro game lovers who have a passion for horse racing, Pocket Stables is just the perfect game. At first glance, this game might look simple, but it actually has many features that make it even more fun.

For starters, you can build training facilities where you can increase your horse’s stats. Additionally, not all horses are the same and your goal should be to find a horse with the right balance of speed, stamina, and intensity.

As you win races, you’ll receive prizes, that can be used to upgrade your stable and give you better ways to breed a faster horse.

It’s fun, casual, and quite cute. Plus, you get to build your horse racing community and hire people that will take care of your stable.

Gaming News

Swiping, Tapping, and Tilting: How Mobile Games Are Played Today

It’s crazy to think mobile games started with super basic stuff like Snake on old-school Nokia phones. Now, thanks to touchscreens and motion sensors, playing games on our phones feels more immersive than ever. Whether it’s swiping to cast spells, tilting to steer race cars, or just furiously tapping buttons, mobile gaming has come a long way from static keypads of the past.

How It Was

In the beginning, little keypads were the only controls we had to work with. Remember playing Brick Breaker on their BlackBerry, anyone? Then, the accelerometer changed everything. Suddenly, we could just tilt our phones to do all kinds of things like aim angry birds, balance stacks of blocks, even steer cars in racing games. Way better than pressing little arrows!

Of course, as screens got more advanced, mobile games exploded into all kinds of genres, from puzzles to 3D adventures. Multitouch displays, in particular, are what really enabled natural feeling gesture controls.

Swiping Changes the Game

These days, swiping is easily one of the most common ways we interact with mobile games. You’ll find it everywhere, from temples you raid in endless runners like Temple Run to baseball diamonds when batting in MLB Tap Sports Baseball. Swiping not only feels super intuitive but also adds velocity and immediacy, perfect for fast-paced games.

Even slower-paced games use swipes for all kinds of game mechanics, like directing troops across battlefields in strategy games such as Clash of Clans. No matter the genre, swiping works because it feels so smooth, direct, and responsive. Not to mention, it’s just plain fun!

Tapping into Gameplay

Tapping will always be one of the best ways we can interact with phones. After all, it’s how we click links, type messages, and snap pics. For gaming, taps are perfect for delivering pinpoint precision. There’s nothing quite as satisfying as nailing a perfect note streak in games like Piano Tiles by tapping right on the beat.

You’ll also find that tapping makes snappy navigation through menus and UI thanks to its accuracy and responsiveness. Most games use taps for activating fundamental stuff like making your character jump, shoot, or interact with objects in the game world. It’s just so reliable!

Hypercasual games, in particular, thrive on simple yet addictive tap mechanics around sorting colors, popping bubbles, merging objects, and the like. When gameplay boils down to pure interactivity, nothing beats good old-fashioned screen tapping.

Getting Physical with Motion Controls

Phones now pack all kinds of motion sensors that track positioning and tilt along multiple axes. It allows for a myriad of gesture controls that add physicality and mimic real actions. For example, you can cast a line by flicking your phone while fishing in Ridiculous Fishing. Steering vehicles in racing games feels super tactile by tilting your phone to control direction. Even party games get in on the action with shaking or wiggling gestures detecting your phone’s movements.

Anything that gets us moving beyond just staring at the screen helps create moments of skill-based mastery. You feel much more engaged pulling off tricky shots in pool games by adjusting just the right angle or keeping teetering structures from collapsing with careful tilting. That sense of physical feedback goes a long way toward gameplay immersion.

Voice, AR, and Beyond

With phone cameras, mics, and sensors improving by the generation, we’re beginning to see radical new control schemes. Augmented reality transforms the world around you into a game environment like we’ve seen with monumental successes like Pokémon GO. Calling plays or audibling routes by literally yelling at your phone has also created hilarious moments playing Madden NFL Mobile. Heck, the camera can even scan objects to import them into games. The possibilities seem endless as technology progresses!

But with all these advancements, the most crucial thing developers can do is make sure their games remain accessible through difficulty settings, customizable controls, and assist modes. That way, anyone can tailor things to their personal playstyle and limitations. Gaming needs to be fun and inclusive for everybody, after all!

With new mobile games flooding app stores every single day, it feels risky trying out some random new title. That’s where special apps like Cash Giraffe come in handy. They actually give you money just for testing out new mobile games with no strings attached!

Where Are We Headed?

It’s anyone’s guess where things go next. Controllers are becoming more common to make mobile gaming feel console quality. Tools like Apple Pencil and Bluetooth styluses could let us draw playfields or game elements. New sensors might even track eye movements for hands-free control. The future is filled with possibilities!

For now, though, as long as developers keep innovating with intuitive tap, tilt, and swipe gestures, mobile games should have no problem staying fun and immersive. Just try not to smash your phone in celebration next time you pull off an epic comeback!

iOS Games

Is it harder to qualify for iOS requirements or Android requirements for apps?

In today’s digital age, mobile applications have become a crucial component of everyday life. They provide users with access to a wide range of services, entertainment, and information at their fingertips. However, creating a mobile app that works seamlessly on both iOS and Android platforms can be a daunting task. Developers need to ensure that their app meets the strict guidelines set by both platforms to ensure a smooth user experience.

The iOS and Android platforms have their own unique set of requirements and guidelines that must be followed for an app to be approved and made available to users. These guidelines include technical requirements, design standards, and content policies, among others. To ensure that an app reaches the largest possible audience, it is crucial that it meets the requirements of both platforms.

In this blog post, we will examine the question of which platform is harder to qualify for, iOS or Android requirements, using a casino app as an example. We will explore the specific requirements for casino apps on both platforms, the challenges developers face in meeting these requirements, and provide insights into which platform is more difficult to qualify for. By the end of this post, readers will have a better understanding of the requirements for developing mobile apps and the challenges faced by developers in meeting these requirements.

Overview of iOS and Android Requirements for Apps

To develop a successful app, it is crucial to understand the guidelines and requirements set by both iOS and Android platforms. Here’s an overview of the general requirements for apps on both platforms:

User Interface Guidelines: Both iOS and Android platforms have their own unique user interface guidelines that app developers must follow. These guidelines provide recommendations on designing app icons, typography, color schemes, and other visual elements to ensure a consistent and user-friendly experience.

Technical Requirements: App developers must ensure that their apps meet the technical requirements set by both platforms. For example, the app must function properly on the latest versions of the operating system, use appropriate security protocols, and avoid unnecessary battery consumption.

Content Policies: Both iOS and Android platforms have policies governing the type of content that can be published on their respective app stores. These policies cover a range of topics, including adult content, intellectual property infringement, and deceptive practices. Developers must ensure that their apps meet these content policies to avoid rejection from the app store.

While the general requirements are similar, the specific guidelines and approval processes for iOS and Android platforms differ in several ways. For example, iOS has a more stringent approval process compared to Android. The App Store review process can take several days, and the approval criteria are often subjective. In contrast, Android has a more lenient approval process, with apps typically available for download on the Google Play Store within a few hours of submission.

Additionally, iOS has a closed ecosystem that limits the apps available to users. Developers must adhere to Apple’s strict policies and guidelines for inclusion in the App Store. On the other hand, Android has an open ecosystem that allows for more flexibility in app development and distribution. Developers can publish their apps on third-party app stores or distribute them directly to users.

Overall, developers must understand the differences between iOS and Android requirements and tailor their development approach accordingly. While both platforms have their unique challenges, meeting their requirements is essential for app success.

Requirements for a Casino App on iOS and Android

Developing a casino app for iOS and Android requires careful attention to platform-specific requirements and regulations. Here’s an overview of the specific requirements for casino apps on both platforms:

Regulations on Gambling Apps: Both iOS and Android platforms have strict regulations on gambling apps, which are intended to protect users from fraudulent activity. Apple only allows real-money gambling apps in certain countries, and developers must hold a valid gambling license in those countries. On the other hand, Android allows real-money gambling apps in many countries, but developers must comply with local laws and regulations.

Policies on In-App Purchases: In-app purchases are a significant source of revenue for casino apps. However, both platforms have policies governing in-app purchases to ensure a fair and transparent user experience. Apple requires all in-app purchases to be processed through its own payment system, which takes a 30% commission on all transactions. In contrast, Android allows developers to use third-party payment systems and takes only a 15% commission on transactions.

Requirements for App Design and Functionality: Both iOS and Android platforms have requirements for app design and functionality. These requirements cover various aspects of the app, including user interface, navigation, and security. For example, apps must use secure authentication protocols and encryption to protect user data.

When it comes to casino apps, there are some significant differences between the requirements for iOS and Android. For example, Apple does not allow apps that offer gambling services to minors, and developers must comply with strict age verification requirements. Android also has age restrictions but allows for more flexibility in the types of gambling apps that can be developed and published.

Another significant difference between iOS and Android is the availability of real-money gambling apps. While iOS only allows real-money gambling apps in certain countries, Android allows these apps to be developed and published in many countries. This can impact the development approach and revenue potential of a casino app.

In conclusion, developing a casino app for iOS and Android requires careful consideration of platform-specific requirements and regulations. While there are similarities in the requirements, there are also notable differences that must be considered. Click here to see these casinos and their respective apps to better understand the design and functionality requirements of casino apps on both iOS and Android platforms.

Challenges of Meeting iOS and Android Requirements for Casino Apps

Developing a casino app that meets the requirements of both iOS and Android platforms can be a complex and challenging task. Here are some of the common challenges that developers face:

Compliance with Regulations: Casino apps are subject to strict regulations on both iOS and Android platforms. This can include requirements related to gambling licenses, age verification, and responsible gambling. Developers must ensure that their apps comply with these regulations to avoid rejection from the app store.

Payment Systems: In-app purchases are a significant source of revenue for casino apps, but the payment systems used by iOS and Android platforms differ significantly. Developers must carefully consider which payment system to use and ensure that they comply with the policies of the platform.

User Interface: Both iOS and Android platforms have unique user interface guidelines that app developers must follow. These guidelines provide recommendations on designing app icons, typography, color schemes, and other visual elements to ensure a consistent and user-friendly experience. However, designing a user interface that meets the requirements of both platforms can be challenging, especially when dealing with complex user interfaces and game mechanics.

Security: Casino apps require robust security measures to protect user data and prevent fraudulent activity. Developers must ensure that their apps use secure authentication protocols and encryption to safeguard user data.

While the challenges faced by developers in creating casino apps for iOS and Android platforms are similar, there are notable differences. For example, Apple has stricter age verification requirements for gambling apps than Android, which can be a significant challenge for developers. Additionally, the payment systems used by the two platforms differ significantly, with Apple taking a 30% commission on all in-app purchases compared to Android’s 15% commission.

In conclusion, developing a casino app that meets the requirements of both iOS and Android platforms can be a challenging task. Developers must navigate complex regulations, payment systems, user interface guidelines, and security measures. While there are similarities in the challenges faced, there are also notable differences that must be considered. By understanding these challenges, developers can create high-quality casino apps that meet the requirements of both platforms.

Conclusion

In conclusion, developing a mobile app that meets the requirements of both iOS and Android platforms can be a challenging task. In this blog post, we explored the specific requirements for a casino app on both platforms, the challenges developers face in meeting these requirements, and provided insights into which platform is harder to qualify for based on the example of a casino app.

We learned that both iOS and Android platforms have unique requirements related to user interface guidelines, technical requirements, content policies, and regulations on gambling apps and in-app purchases. While there are similarities in the requirements, there are also notable differences that must be considered.

In terms of which platform is harder to qualify for, the answer may vary depending on the specific app being developed. However, in the case of a casino app, iOS is generally considered to be the more challenging platform due to its stricter regulations, more stringent approval process, and higher commission rates for in-app purchases.

As mobile app development continues to evolve, it is essential for developers to stay up-to-date on the requirements and guidelines set by both iOS and Android platforms. By doing so, they can create high-quality apps that meet the needs of their target audience.

We encourage readers to share their experiences developing apps for iOS and Android platforms in the comments below. Your insights can help others navigate the challenges of mobile app development and contribute to the continued growth of the mobile app industry.

-

Guides5 years ago

Guides5 years ago6 Proven Ways to Get more Instagram Likes on your Business Account

-

Mainstream10 years ago

Mainstream10 years agoBioWare: Mass Effect 4 to Benefit From Dropping Last-Gen, Will Not Share Template With Dragon Age: Inquisition

-

Mainstream6 years ago

Mainstream6 years agoHow to Buy Property & Safe Houses in GTA 5 (Grand Theft Auto 5)

-

Casual2 years ago

Casual2 years ago8 Ways to Fix Over-Extrusion and Under-Extrusion in 3D Printing

-

Mainstream12 years ago

Mainstream12 years agoGuild Wars 2: The eSports Dream and the sPvP Tragedy

-

Guides10 months ago

Guides10 months agoFree Fire vs PUBG: Comparing Graphics, Gameplay, and More

-

iOS Games2 years ago

iOS Games2 years agoThe Best Basketball Games for IOS

-

Gaming News1 year ago

Gaming News1 year agoSwiping, Tapping, and Tilting: How Mobile Games Are Played Today