Features

Five Ways Morality in Games Needs to Be Fixed

Moral issues and choices are extremely commonplace in games today and, for whatever reason, often touted as a major selling point that totally alters the direction of the game’s story and you, the player, are the author. I would say there’s no easier way to add a layer of depth and engagement by introducing ethicality and engaging the player in a way that allows them to craft their own personal narrative. The problem with this, unfortunately, is that the scope of morality is vast and indefinite. It’s conceptually ambitious on a level that I’m not even entirely sure could ever be fully realized because morality, as well as being nebulous, is remarkably complicated. Moral choices manifest in such a way that it robs the game of its ability to be a whole and well-rounded experience so if they’re only going to become more prevalent, then they will need to be neatly nuanced.

Following are my 5 ideas on what the issues of morality in games are, and how they might be fixed:

1. Good or Evil Are Your Only Actual Choices

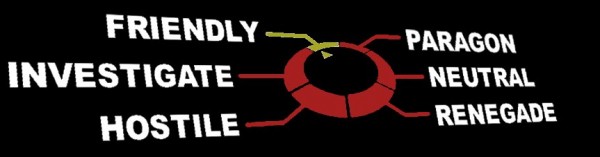

If one is to consider the essence of goodness or evilness, what qualities might they choose? What makes goodness or evilness primarily and unequivocally that which we consider them to be? You’d most likely, at least not realistically, describe someone you personally know as just evil or good. Obviously, there are attributes to be associated with either good or evil, but what? For the purpose of games where you never actually become “the villain”, per se, like Mass Effect, your choices of attributes are essentially between selfishness and altruism. But on the other end of the spectrum where you have a choice between hero and villain, as in inFamous, this is a little more questionable because your choices then are rationality or sociopathy which is a total disservice to iconic villains and heroes.

In both series, however, you are locked out of options or special abilities if you don’t pick a side and stick with it. Gating content behind moral choices is understandable, to a degree, because the furthest reaches of the morality meter are more often than not just a few little extras to reward players for their consistency. But then, doesn’t that sort of take the decision out of your hands? Why would I willingly make my character less powerful? That’s sort of the catch-22 by intertwining moral choices with other gameplay mechanics. inFamous is especially guilty of this because if the Evil power is objectively better than the Good power then my decision is no longer grounded in the framework of the game’s narrative but rather its metagame for lack of a better term.

You can’t even abstain from these two choices because if the choice isn’t outright dichotomous then you’re being punished for neutrality, which is certainly a valid position to take. Mass Effect 2 calls upon you to end a quarrel between two party members and if your paragon/renegade score isn’t high enough then you effectively lose one of the character’s loyalty, meaning that they are essentially guaranteed to die at the final mission. inFamous will just lock you out of nearly every single power in the game if you don’t pick a side. You shouldn’t be punished explicitly because you didn’t choose the ‘appropriate’ good guy/bad guy answer.

2. Villains Are Totally Unnatural

Though I suppose that could be debated. When a story has you playing as some everyman or ordinary person thrust into incredible and dangerous circumstances, they are still at heart an ordinary person. inFamous: Second Son stars Delsin Rowe, a mid 20s slacker who has an issue with authority. When his amazing superpowered abilities awaken, he’s excited and enthused. He even likens himself to a superhero. So, why all of a sudden does he want to become a psychopathic killer? When presented with two options, one being wildly extreme and the other rational, why would I ever naturally pick the extreme one?

What reason would Delsin have to ‘corrupt’ someone when he has faced alarmingly little prejudice and has no viable compulsion to just start willfully killing innocents and recruiting others to help him? He doesn’t have one, and that’s why being a villain in inFamous is nonsensical.

Most normal people prefer ‘goodness’ as they see it. I bet you’d rather live in a country where the government wasn’t despotic and forcing the citizens into poverty or driving them into the middle of town to beat them. Likewise, if you saw a little girl who looked weird but was otherwise harmless a la BioShock, I doubt your first instinct would be “I’m going to brutally murder this child”. Disregarding the fact that ‘evil’ on its own is a terrible descriptor, senseless murder is just completely immoral and malicious. So why is that typically the result behind ‘evil’ actions and choices? Because it’s clear that no rational person would ever do these things and to be evil is to be abnormal?

If evil is that which we consider to be undesirable, why does the list end at “impulsive and violent”? There is a myriad of other ways to communicate ‘evilness’, so why stop at the most obvious? Too few are the games where I can be manipulative and cunning with a veneer of friendliness and sincerity. Instead, we get a near farcical interpretation of ‘evil’ which is just killing everyone for no apparent reason. I’d call that insane before I called it evil.

Mass Effect 2 offered a new style of making off-the-cuff decisions by introducing interrupts to conversations. At the press of a button, Shepard would launch into either a paragon or renegade action that would change the situation. That sounds like a great idea, both fluid and more natural, but the two often don’t mix well. Shepard can use a renegade interrupt, despite having fully invested into paragon, and just assault a reporter but then later console a friend after she finds her father dead.

Out of those two, which do you see yourself actually doing? It’s easier to be good because that’s just sort of a natural inclination. Even if you’re astoundingly cynical it’s easier to walk past the orphanage, thereby ‘saving’ it and gaining the approval of your peers, then it is to burn it down. You’re not just going to punch a reporter for asking you difficult questions, that’s just totally out of the realm of reality unless you just are totally indifferent to social rules.

3. It’s An Illusion of Choice

In BioShock, at least, you are locked out of some of the more powerful skills and abilities which is in and of itself a statement about the ‘evil’ path, I suppose. But then is it really a worthwhile choice? Let’s break it down into what the system more or less represents: Do you want more game or less? Well, you probably want more so then your hands are tied into choosing the good option. You’re not really free to do or say what you want because you might irrevocably lose something important so you have to cautiously pick a side and stay on it. In doing so, you’re removed from the game and the character is no longer an extension of yourself.

Not only that, but it’s not like the story ever really changes to the point where your actions have done anything. No matter what you do, you end up going to the final battle or whatever the climax of the game is and it’ll be the same–though your character might be more aggressive about it or something like that. The thing is, moral choices can’t properly function in a narrative that has an established end point. If I’m tasked with saving the world but decide not to do it then that would ostensibly be the ‘evil’ choice but then there’s no game because I’ve ended it prematurely. Choosing to save the world, then, is the ‘good’ option but if my character has no desire to save the world then I’ve disengaged myself from the character, their world, and am just playing a game.

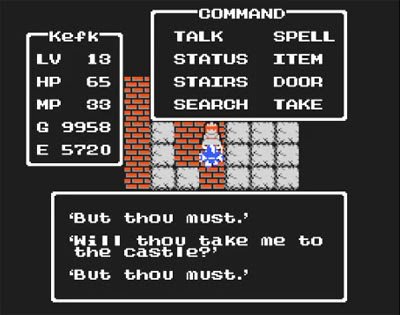

JRPGs are often criticized for “but thou must” styled options, but all of the games that proudly display their moral choices are victims of it too. I still have to choose something to progress the game, I’m just allowed to be a jerk about it if I want. Are those qualitatively the same? Maybe, maybe not, but the fact of the matter is that you still don’t really have a choice in the matter. The story moves at your behest and not before that. But maybe that’s not a fair criticism because games typically need a climax so it’s unrealistic to expect a breadth of decisions leading to something entirely different each and every time.

4. It’s Simply Too Ambitious

For a series as immense as Mass Effect, there was no realistic way for them to account for every single permutation that a player’s decisions and it failed to do so beyond a little reference to your actions in past games. The story did not meaningfully change nor did its ending. Morality in games is theoretically fine but there’s just no possible way for it to ever reflect the complexities of real-life morality and the way it influences the people around you.

It’s a problem with perception. Some games, like Dragon Age: Origins, operate on a scale of approval individually on a party member to party member basis. Where morally righteous Alistair approves of your benevolence, the unscrupulous witch Morrigan might just think you’re plodding around and wasting time when you could get results now. I think that’s better but not exactly ideal, because that system is very easily gamed by just foisting presents at random. Obviously, if I punched your grandmother in the nose, showering you with gifts probably wouldn’t make you consider me a good person. Why, then, are video games different in this respect? It’s a more authentic role-playing experience for your actions to have tangible consequences that no amount of material wealth will change.

With this being the case, I’m not sure if it would ever truly be possible to emulate this. There are so many variables and unknowns involved with almost every interaction and where it can lead you. Video games can’t realistically accomplish that, and maybe they’re better off not doing that. But then, ultimately, is it really a moral choice being made?

5. Morality is Relative

Disregarding everything I’ve just said, an option can’t really be objectively good or evil because those qualities can’t realistically exist in such a way that they are easily agreed upon. Your final choice in the original Mass Effect is to let the major standing political power, composed entirely of aliens, in the galaxy die at the cost of several thousands of human soldiers and citizens. Of course, you can make the opposite decision and save the humans and let the politicians die.

This is a good example of what a moral choice should be. Although the game presents saving the politicians as the ‘good’ choice and saving the citizenry the ‘evil’ choice, there is a case to be made that reverses both of these positions. This is the groundwork of a compelling moral decision because there is something to risk. One is ethically appealing and the other more pragmatic, to an extent, but framing options as ‘good’ or ‘evil’ is a mistake that games would do well to correct. A character will organically do what they believe to be right because it aligns with their convictions rather than a preternatural adherence to some moral creed of goodness or adherence to evil.

Moral choices have the power to create something incredibly meaningful and games are the perfect medium with which to explore that potential. None of this is to say that moral choices should disappear from gaming full stop, because there are several noteworthy instances where these ‘moral choices’ aren’t presented or established in a way that they lend themselves to dichotomy. TellTale’s The Walking Dead is the quintessential example of a game that uses choice well because goodness and evil are totally irrelevant struggles when they cease to exist in a world that has become viciously survivalist-like in nature. Your decisions shape Lee’s character and how he is perceived by others. Some may like him, others distrust him. Some will want to help him, while others will turn a blind eye to the dangers he finds himself in. Virtually all of Lee’s choices are timed so you, the player, must stay engaged with him rather than let him zone out for hours with his eyes flitting about and dancing between two options. Alpha Protocol, which was a very unfortunately misunderstood game, operated similarly to great effect.

The Witcher eschews those organic, conversational, and more immediate options for similar dichotomous ones as Mass Effect but then does them well by leaving the player wondering what might have happened if they chose differently. That is what a moral choice should be. It needs to be tough, thought-provoking, and worth questioning.

Fixing some issues with moral choices isn’t possible at the moment. Accounting for each action and combination of actions that a player might take is probably worlds away. What can be done, however, is to eliminate boring and absurd ‘moral’ choices and replace them with morally grey and tough decisions that are equally valid no matter what. Those are the decisions that foster good writing and character development because it speaks volumes more about your character than picking an alignment and sticking with it. I’m sure there are plenty of games that incorporate these choices perfectly but when it comes to the big AAA games touting their own choices and narratives, they just aren’t up to snuff.

Features

Exploring k2.vox365: Revolutionizing Digital Communication and Collaboration

In today’s fast-paced digital world, businesses and individuals alike are constantly looking for efficient ways to communicate and collaborate. Enter k2.vox365, a powerful platform designed to streamline communication, enhance collaboration, and boost productivity. With its comprehensive suite of tools, k2.vox365 is rapidly becoming a preferred solution for businesses, educational institutions, and remote teams looking to stay connected and organized.

What is k2.vox365?

At its core, k2.vox365 is a unified communication and collaboration platform that brings together messaging, video calls, and project management into one seamless experience. Unlike traditional tools that require switching between different apps for emails, chat, and file sharing, k2.vox365 integrates all these features into a single, easy-to-use platform. This all-in-one solution reduces complexity and makes communication more efficient for teams of all sizes. Since its inception, k2.vox365 has gained traction for its robust functionality and user-friendly interface, positioning it as a strong competitor in the digital communication space.

Core Features of k2.vox365

A. Unified Messaging

One of the standout features of k2.vox365 is its unified messaging capability. The platform allows users to manage all forms of communication — whether it’s emails, instant messages, or video calls — from one place. Users can easily transition between messaging modes without the hassle of switching between apps. This is especially beneficial for teams who need real-time communication but also rely on email for formal exchanges.

B. Collaboration Tools

In addition to communication, k2.vox365 offers a suite of collaboration tools that help teams work together effectively. Whether it’s real-time document editing, file sharing, or managing tasks and projects, k2.vox365 enables seamless collaboration across departments. Teams can work on the same document simultaneously, leaving comments, making changes, and tracking progress all in one place, reducing the need for endless email chains or disjointed software solutions.

C. Cloud-based Accessibility

With cloud-based accessibility, k2.vox365 ensures that users can access their work from any device, at any time. Files, messages, and projects are all stored securely in the cloud, allowing for easy access whether you’re in the office or working remotely. This also means that data is continuously backed up, minimizing the risk of losing important information due to technical failures.

How k2.vox365 Enhances Business Productivity

One of the biggest benefits of k2.vox365 is its ability to boost business productivity. By consolidating communication, collaboration, and project management into one platform, teams can work more efficiently. The unified approach reduces downtime spent switching between apps, looking for files, or chasing down project updates. This streamlined workflow allows employees to focus on what truly matters: delivering results. Furthermore, the real-time collaboration tools improve team coordination, ensuring everyone stays on the same page.

Security and Data Protection in k2.vox365

In an age where data breaches and cyber threats are rampant, k2.vox365 prioritizes security and data protection. The platform uses end-to-end encryption to ensure that all communication, whether it’s messaging, video calls, or file sharing, remains secure. Additionally, k2.vox365 complies with important data privacy regulations, such as GDPR, offering peace of mind to businesses concerned about safeguarding sensitive information. The platform also includes advanced measures to protect against phishing attacks and malware, ensuring a secure communication environment for all users.

Industry Applications of k2.vox365

k2.vox365 is not just for businesses. Its versatility makes it an excellent choice for a variety of industries:

A. Corporate Environments

In corporate settings, k2.vox365 is used to streamline internal communication and project management. Its integrated tools allow departments to work more efficiently, keeping track of tasks, deadlines, and project progress. The platform’s unified messaging system also makes it easy for team members to stay in constant communication, regardless of their location.

B. Educational Institutions

For educational institutions, k2.vox365 provides a seamless way to support virtual learning. Teachers and students can communicate through video calls, share files, and collaborate on assignments in real time. The platform’s task management tools help students stay organized, ensuring that assignments are completed on time.

C. Remote Work

With remote work becoming the norm, k2.vox365 plays a crucial role in enabling teams to stay connected no matter where they are. Its cloud-based services ensure that employees can access files and communicate with colleagues from any device, making it a perfect tool for global teams and freelancers who need to collaborate across time zones.

Comparing k2.vox365 with Competitors

When compared to other popular platforms like Microsoft Teams, Slack, or Zoom, k2.vox365 holds its own. While Microsoft Teams and Slack are well-known for their chat-based collaboration, k2.vox365 excels with its broader set of features, including unified messaging, integrated project management, and cloud accessibility. Zoom, a leader in video conferencing, offers a more limited scope compared to k2.vox365’s full suite of tools. The strength of k2.vox365 lies in its ability to combine multiple communication channels into one platform, giving it an edge over these single-function competitors.

User Testimonials and Case Studies

Many businesses have seen tangible benefits after adopting k2.vox365. For instance, XYZ Corporation, a mid-sized tech company, reported a 20% increase in team productivity after switching to the platform. The real-time collaboration tools helped employees reduce delays and stay better aligned on projects. Similarly, ABC University found that k2.vox365 significantly improved communication between students and faculty, especially during the shift to remote learning.

Pricing and Subscription Plans

k2.vox365 offers flexible pricing tailored to different business needs. For small businesses, there’s a basic plan that includes essential features like messaging and file sharing. Larger enterprises can opt for more advanced plans, which offer additional features like enhanced security, advanced project management tools, and increased cloud storage. There are also customized plans for educational institutions, allowing them to access the platform’s full suite at a discounted rate.

Future Prospects for k2.vox365

The future looks bright for k2.vox365. The platform’s developers are continuously working on new features, including AI-driven productivity tools and more advanced security protocols. As businesses continue to shift towards digital solutions, k2.vox365 is poised to become a leader in the communication and collaboration space. With plans to expand its global presence, the platform is set to make a significant impact in the market in the coming years.

Conclusion

In conclusion, k2.vox365 is an innovative platform that provides a comprehensive solution for communication and collaboration. With its unified messaging system, real-time collaboration tools, and cloud-based accessibility, it is designed to help businesses, educational institutions, and remote teams stay connected and productive. As digital communication continues to evolve, k2.vox365 is well-positioned to lead the way, offering the tools and features necessary for success in today’s fast-paced world.

Casual

Creative Ideas for Best Technology Instagram Post 2024

Are you facing difficulty in engaging your audience with tech posts on Instagram? As social media platforms have transformed into virtual marketplaces, brands recognize the need to showcase expertise through engaging content.

Platforms like Instagram empower connecting with worldwide audiences through captivating visual stories. But, it is quite a daunting task to work and many move ahead to buy Instagram followers as well.

Contemporary consumers scarcely have time for promotion lacking substance. Hence, creatives demand integrating education with entertainment for intrinsically motivating connections. This is why in this post, we discuss top ideas for your tech-posts on Instagram. Read on.

Top Instagram Post Ideas for Technology in 2024

There are many creative and unique ways to catch attention for your technology posts on Instagram. Below we discuss some of the most popular ones that can certainly get all eyes on you.

I. Using Tech Products as Props

Showcasing the ergonomic elegance of newest smartphones through lifestyle photos depicting them harmonizing with modern interiors signifies how technologies enhance lives unobtrusively.

Flat lays carefully arranging phones alongside complementary gadgets like smartwatches and earbuds exhibits compatible accessories apt for varied tasks. Close-up shots exploring interesting details on laptops or cameras from unique angles pique curiosity towards innovative engineering.

Illustrations envisioning people multitasking efficiently through integration of different devices tells stories audiences relate to. Including props within realistic settings displays practical applications beyond technical specifications.

II. Behind the Scenes Photos of Tech

Sneak peeks hinting at cutting-edge features of anticipated device launches grant exclusivity while cultivating hype. Well-lit workplace photographs portray engineers concentrating on prototyping components and inspire admiration.

Snapshots capturing programming teams collaborating wirelessly on interactive whiteboards through mobile apps demonstrate streamlined productivity. Infographics adorning clean designs simplify explaining complex algorithms behind facial recognition or data analytics in accessible language.

Short videos taking viewers inside futuristic factories reveal meticulous manufacturing processes with a sense of intimacy.

III. Infusing Tech with Humor

Lighthearted memes humorously portraying predictable reactions to everyday tech troubles provide comic relief to stressful scenarios. Relatable situations humorously presented divert from serious sales pitches.

Personified tech objects in comical misadventures amuse audiences through humanizing technology. Satires skewering society’s obsession with smartphones in a tongue-in-cheek manner encourages shares to spread smiles. When infused judiciously, humor aids connection by sparking emotions beyond sales.

IV. Showcasing the Human Side of Tech

Introducing changemakers through portraits celebrating their groundbreaking work nurtures admiration. Profiles highlighting individuals transforming lives through accessible education technologies promote empowerment.

Environmental initiatives leveraging automation to offset carbon footprints brings a humanistic face to sustainability efforts. Impactful community projects excelling through connectivity showcase technology uplifting society versus solely profit motives.

Sensitively showcasing stories of overcoming challenges strengthens bonds between brands and audiences.

V. Visual Presentations of Tech Topics

Creative arrangements of flat lays showcasing virtual or mixed reality controllers provides an experiential feel of the immersive tech itself. Sequential photos arranged like puzzle pieces or in grids present complex technical concepts through visual storytelling.

Infographics leveraging minimalist aesthetics simplify explaining blockchain or cloud computing. Illustrations personifying IoT appliances in a “day in life” routine brings relatability to innovations perceived as complex. Data visualizations comparing tech trends succinctly impart industry insights.

VI. Leveraging Trending Tech Themes

Imaginative demonstrations of artificial intelligence streamlining lives pique intrigue towards groundbreaking research. Showcasing developments in robotics, VR or internet of things solving pressing issues cultivates social purpose beyond sales.

Highlighting startups leveraging cutting-edge innovations attracts investors and talent. Curated reels condensing key takeaways from tech summits grant exclusive access. Tactical hashtags around concepts ranging from 5G to cybersecurity optimize discovery of relevant audiences worldwide.

Unique Ways To Boost Engagement

With competition so fierce, it becomes difficult to keep your audience engaged with your post. Below we discuss some essential tips that can make things easy for you. Take a look:

● Researching Optimized Hashtags

Analyzing hashtag clusters witnessing frequent usages around niche conversations aids discovering appropriate tags aligning with targeted audiences. Careful hashtagging aids discoverability and spreads messages to receptive crowds naturally.

● Optimizing Images For Social Formats

Adjusting photos to square dimensions suitable for Instagram feeds and story formats preserves visual quality and context. Proper sizing and cropping focuses viewer attention on essential elements.

● Scheduling Around Peak Engagement Timings

Identifying timing patterns of highest follower activities through analytics aids posting when most eyeballs will likely notice new updates. Repurposing top performing content as story highlights retains visibility.

● Reviewing Engagement And Follower Insights

Regularly evaluating metrics like likes, comments, saves and follower growth rates aids comprehending reception and refining strategies. Tracking identified hashtag or location based communities’ interests guides customized content.

● Partnering With Key Influencers

Reaching wider audiences through cross-promotional shoutouts with popular domain figures expands networks. Collaborations establishing brand authority through third party endorsements bolster credibility.

Final Thoughts

In summary, effectively leveraging visual creativity fueled by data-driven decisions establishes technology companies, alongside support from a dedicated social media growth agency like Thunderclap.it, as thought leaders amid competition on platforms like Instagram.

Consistency, authenticity, and nurturing communities through meaningful interactions are crucial for driving organic visibility and achieving superior returns on social media. While maintaining technical excellence is essential, emotionally connecting with audiences through social missions and humor helps build a loyal following and fosters trust in this experience-driven world.

Features

Exploring Valorant eSports Stats: Unveiling the Metrics Behind Competitive Excellence

In the rapidly expanding realm of Valorant eSports, statistical analysis plays a pivotal role in understanding player performance, team dynamics, and the strategic nuances that define success in competitive play. This article delves into the significance of Valorant eSports stats, their impact on the competitive landscape, and how they empower players, teams, and fans alike.

Key Metrics in Valorant eSports Stats

Valorant eSports stats encompass a wide array of metrics that provide insights into player proficiency and team strategies. These include individual performance indicators such as kill-death ratios (K/D), average damage per round (ADR), headshot percentages, and assist counts. Team statistics such as round win percentages, first blood percentages, and economy management efficiency further illuminate strategic strengths and areas for improvement.

Analyzing Player Performance and Contribution

For professional Valorant players, statistics serve as a critical tool for evaluating individual performance and contribution to team success. By analyzing metrics like K/D ratios and ADR, players can assess their impact in securing eliminations, dealing damage, and supporting team objectives. This data-driven approach enables players to identify strengths to leverage and weaknesses to address, enhancing their overall effectiveness in competitive matches.

Strategic Insights and Adaptation

Valorant eSports stats provide valuable strategic insights that shape team tactics and gameplay adaptations. Coaches and analysts analyze statistical trends to optimize agent selections, refine map strategies, and counter opponents’ playstyles effectively. The ability to leverage data-driven decision-making empowers teams to evolve their tactics, adapt to meta-game shifts, and maintain a competitive edge in the dynamic world of Valorant eSports.

Tracking Tournament Trends and Meta-Game Evolution

Beyond individual matches, Valorant eSports stats track broader tournament trends and meta-game evolution. Historical data on agent pick rates, map preferences, and round outcomes reveal emerging strategies and meta-shifts over time. This analytical depth allows teams and analysts to anticipate trends, innovate strategies, and stay ahead of competitors in high-stakes tournaments and league play.

Fan Engagement and Spectator Experience

Valorant eSports stats enrich the spectator experience during live broadcasts and tournament coverage. Fans can follow real-time updates on player performances, compare stats across matches, and engage in discussions about standout plays and strategic decisions. Interactive platforms and statistical dashboards enhance viewer engagement, fostering a deeper connection with the competitive narratives unfolding in Valorant eSports.

Impact on eSports Betting and Fantasy Leagues

Valorant eSports stats play a crucial role in eSports betting markets and fantasy leagues, where informed decision-making hinges on statistical insights. Bettors and fantasy league participants leverage player and team stats to assess form, predict match outcomes, and manage their investments strategically. Real-time updates and comprehensive data analysis enhance the strategic depth and excitement of eSports engagement for fans worldwide.

Technological Advancements and Data Visualization

Advancements in technology have revolutionized how Valorant eSports stats are accessed and analyzed. Streaming platforms and eSports websites offer sophisticated data visualization tools, interactive heatmaps, and player performance overlays that enhance the depth and accessibility of statistical analysis. These technological innovations provide analysts, commentators, and fans with enhanced insights into gameplay dynamics and strategic decision-making.

Future Innovations in Statistic Analysis

As Valorant continues to evolve as an eSports powerhouse, the future of statistical analysis promises further innovations. AI-driven predictive analytics, enhanced machine learning algorithms, and real-time performance tracking technologies are poised to revolutionize how eSports stats are processed and utilized. These advancements will elevate the precision, depth, and predictive capabilities of statistical analysis in Valorant eSports, shaping the future of competitive gaming.

-

Guides5 years ago

Guides5 years ago6 Proven Ways to Get more Instagram Likes on your Business Account

-

Mainstream10 years ago

Mainstream10 years agoBioWare: Mass Effect 4 to Benefit From Dropping Last-Gen, Will Not Share Template With Dragon Age: Inquisition

-

Casual11 months ago

Casual11 months ago8 Ways to Fix Over-Extrusion and Under-Extrusion in 3D Printing

-

Mainstream12 years ago

Mainstream12 years agoGuild Wars 2: The eSports Dream and the sPvP Tragedy

-

Guides8 months ago

Guides8 months agoExplore 15 Most Popular Poki Games

-

Mainstream6 years ago

Mainstream6 years agoHow to Buy Property & Safe Houses in GTA 5 (Grand Theft Auto 5)

-

Uncategorized4 years ago

Uncategorized4 years agoTips To Compose a Technical Essay

-

iOS Games1 year ago

iOS Games1 year agoThe Benefits of Mobile Apps for Gaming: How They Enhance the Gaming Experience